National Architecture and Urban Design Competition

Honorable Mention

Between the Designed and the Self-Formed

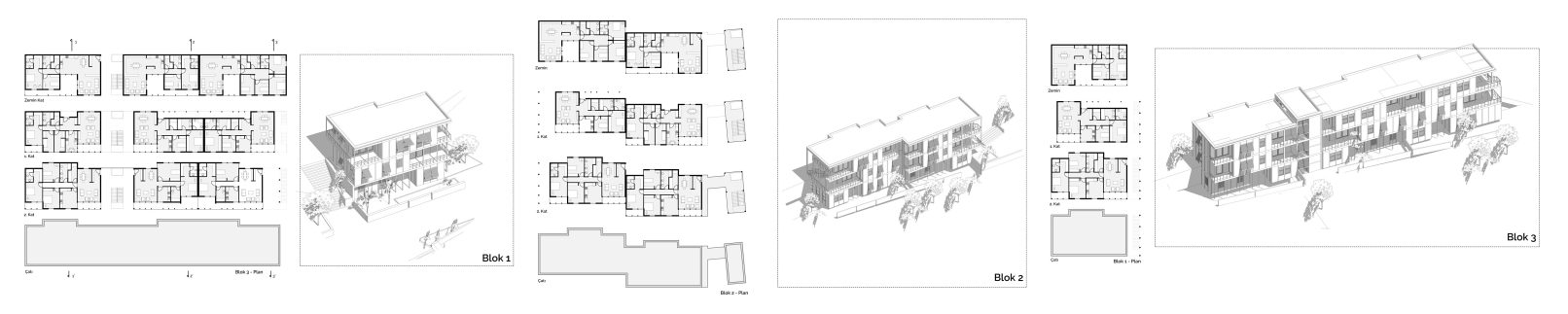

For the mind, establishing an orthogonal layout appears to be the most consistent and rational path. Yet this rigid order often carries a hardness that overwhelms the user, diminishes scale, and excludes the human presence.

Walking through streets that “feel as if drawn with a ruler”, as the elders would say, creates a sense of causelessness. The view does not change with each step. The perspective stays fixed, no surprise appears. Within this monotony, the individual struggles to find a scale that belongs to them.

In traditional neighborhoods, however, houses take shape not on a drawing board but within life itself, guided by the topography. Streets bend, flow naturally, offer a new direction, a new image, a new reason for each step. Movement becomes a ritual. Even long distances feel short.

Here, the human scale is defining. There is a distance one can walk in a single breath with patience. These distances connect through small widenings, allowing the street to breathe. A cluster of roughly forty households forms the essential unit of both social and spatial organization.

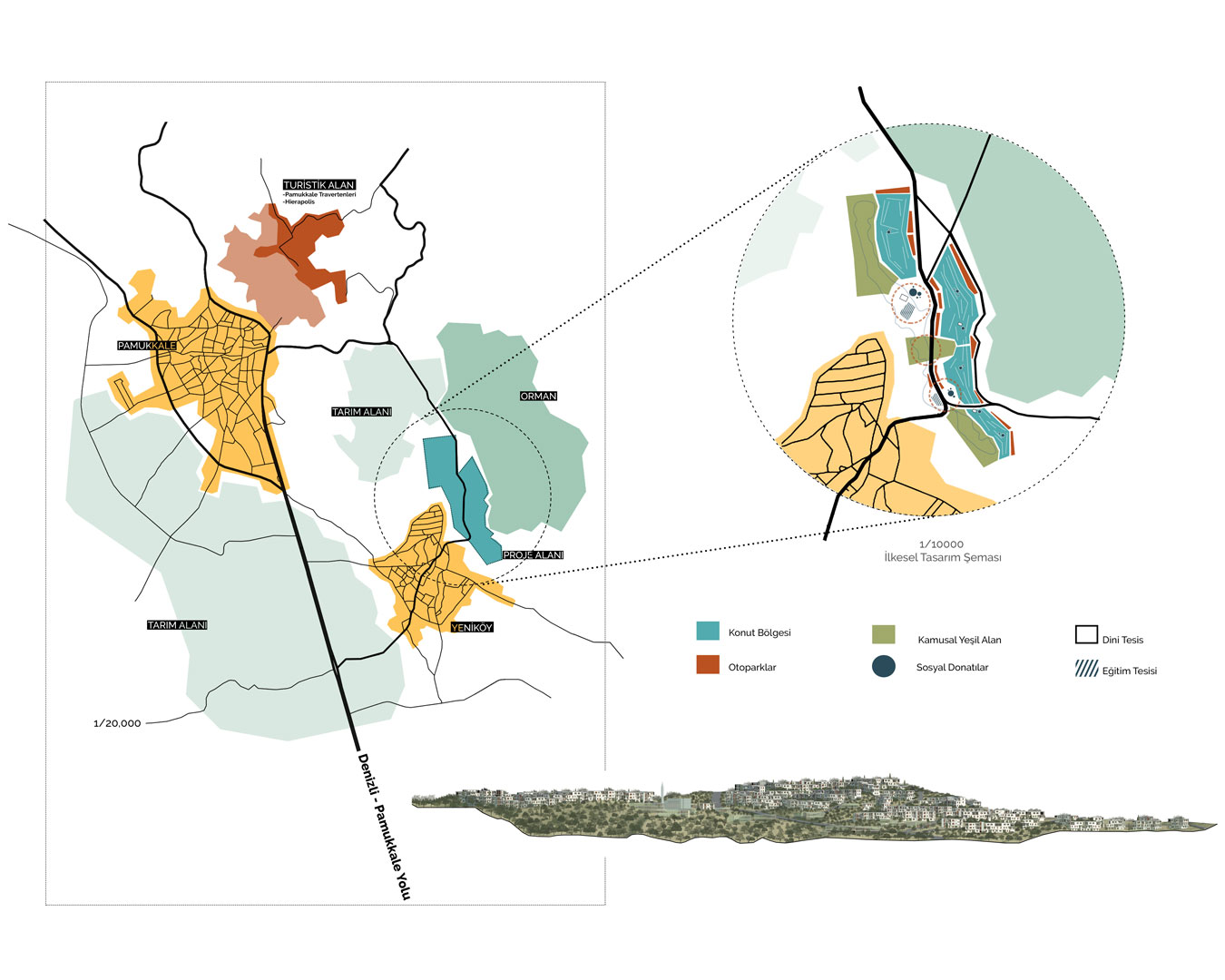

Context and the Natural Setting

In hot and humid regions, settlements often rise to the upper slopes to benefit from the cooling winds. Buildings positioned parallel to the terrain minimize both intervention in nature and construction costs.

The wind becomes a guide for life. Buildings are therefore placed not in a single linear axis but in staggered arrangements. In this way, each structure benefits equally from the breeze, enabling natural ventilation through opposing windows and upper openings. Cooling occurs without energy consumption.

Shade is as crucial as wind. Elements such as eaves, overhangs, bay windows, and eyvans protect the building while creating shaded, livable outdoor spaces. Sun-shading surfaces prevent interiors from overheating and help the building cast its own shadow.

Visibility and Privacy

The staggered layout preserves not only comfort but also privacy. Each home finds its own orientation, forming a relationship with the landscape without opening directly onto another. It is an unseen boundary that nonetheless shapes tranquility.

Instead of a single, uninterrupted street perspective, diversity enriches spatial perception. Structures placed on different axes create a streetscape that complements rather than confronts itself.

Planting and the Economy of Shade

Landscaping around the buildings is not merely aesthetic; it is functional. Shade cools, softens the environment, strengthens privacy, and reduces the heat-island effect. Every tree and every patch of shade carries a practical generosity.

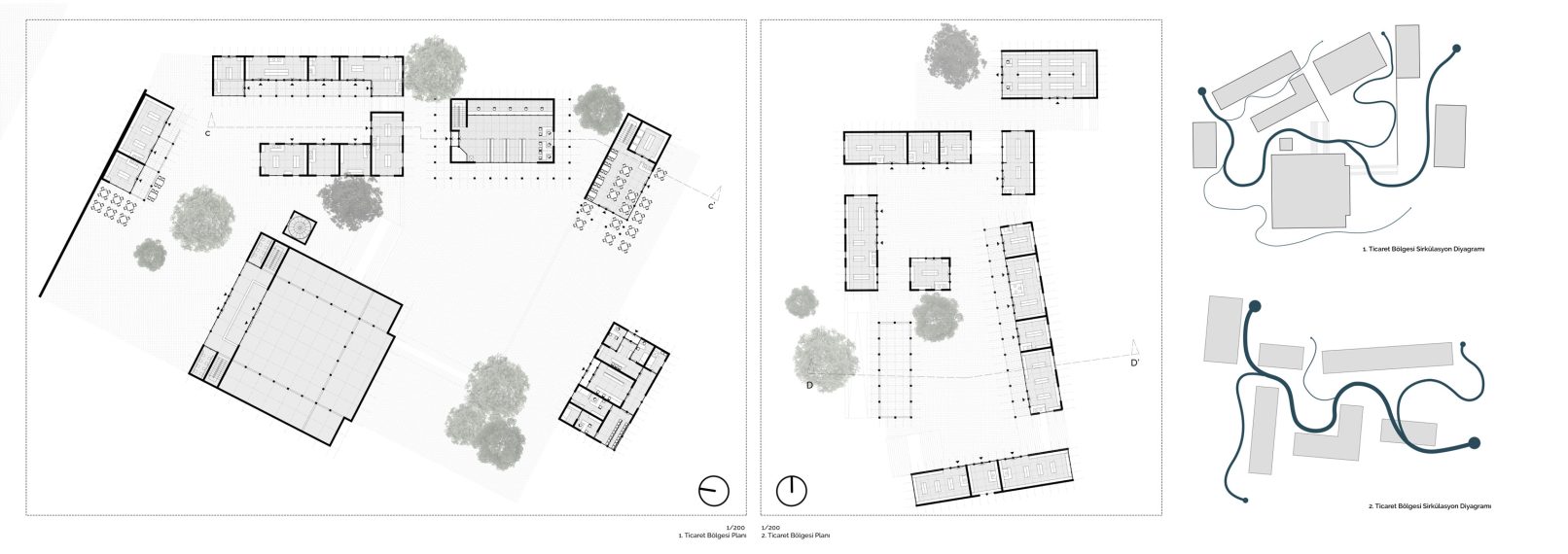

The Idea of the Neighborhood

A neighborhood is not simply a cluster of houses; it is a field of daily interaction. Small-scale commercial units, a masjid, a park, a coffeehouse etc. These elements set the rhythm of life. The neighborhood has no single focus. Life does not gather in one place; it disperses, spills into the street.

This dispersion is not disorder, it is the richness of life. The presence of many small and evenly distributed functions helps the neighborhood remain at a human scale.

Modular System

The settlement is designed around a 120 × 120 cm modular grid. This system aims to generate diversity within an underlying order. Modularity creates multiplicity within unity. While the orthogonal framework provides a rational skeleton, it allows buildings to gather in a more flexible, more natural composition.